In America, the draft plays a huge part in defining the career of a player and the success of organisations involved in picking that player. For this reason, the evaluation of a players potential, ceiling, or upside is big business.

A number of draft experts are employed to develop algorithms focused on (amongst other things) a players performance in his college games and an athletic combine (a series of athletic tests such as vertical leaps and sprints designed to test an athletes raw athleticism), the thought being that these algorithms might help decisions on the potential of players. A huge number of statistics are also employed as part of this process, experts might evaluate a players playing IQ, assist stats, turnover stats, points per game - these metrics are invaluable in the process of comparing apples with apples.

In Rugby, we are far less developed in the assessment of potential. Potential for most Rugby writers is a word used as a crutch for lazy journalism. Which in fact leads me to the first argument in favour of Michael Hooper, and the subject of the first part of the series. Michael Hooper is young, and therefore has potential to be great.

Well, does he? Undoubtedly it is logical that if a player starts young he has a long time to play the game (and therefore maybe to improve). But it does not

necessarily follow that he will improve, in fact he could regress, plateau or simply be replaced by the next big thing.

In this post, I want to analyse the relevance of age to the potential of Michael Hooper (ie this analysis won't necessarily stand for all players, but there may be some general application). First, I am going to talk about age and then move on to analysis of potential.

Michael Hooper is very young. He recently had his 23rd birthday (DOB: 29/10/91). He has achieved a lot since his debut against Scotland in June 2012. He is the youngest captain of the Wallabies since Ken Catchpole in the 60's. He has amassed 38 caps, a John Eales Medal, and a Wallabies Rookie of the Year Award.

As a way to track the possible length of career we might expect from Michael Hooper I have looked at the age of flankers at retirement (or close to retirement) from national teams. This is a crude attempt to estimate the amount of time Hooper has to grow, decline or plateau.

The sample base is taken from top tier IRB nations like the Wallabies, and all during the professional era. The sample aims to take into account injuries across a number of players (and therefore games etc), it also includes caps to illustrate the different playing loads on players.

Richie McCaw

Age: 33 years old (DOB:31/12/80)

Retirement: Still playing

Active playing years: 13 (and counting)

Caps: 135

George Smith

Age: 34 years old (DOB:14/7/80)

Retirement: Retired from international Rugby in 2013

Active playing years: 10

Caps: 111

Richard Hill

Age: 41 years old (DOB:23/05/73)

Retirement: 2008

Active playing years: 11

Caps: 71

Schalk Burger

Age: 31 years old (DOB:13/04/83)

Retirement: Still active

Active playing years: 11

Caps: 73

Thierry Dusatoir

Age: 32 years old (DOB:18/11/81)

Retirement: Still active

Active playing years: 8

Caps: 65

So from our base we can take the following statistics:

- Average age at retirement = 33.6 years (for the players defined as still active, I added a modest single season to their current age)

- Average active playing career = 11.2 (for the players defined as still active, I added a modest single season to their current age)

- Average caps = 94 caps (for the active players I added a modest 5 caps in line with my adjustment above for one extra season).

Using these figures we see that for our sample base the average player began his career aged around

22, played on for

11 seasons at a rate of roughly

8 games a year (this of course includes the RWC which pulls that figure out a little bit).

Bringing this back to Michael Hooper. Michael should play until he is

33 years old, which would be in line with the sample retirement age. This would equate to a playing career of

12 years (just above the sample rate). It is not unreasonable to assume he would play beyond these statistics. Given he has received 38 caps in little over 2 years (ie 19 caps a year), on our sample rate of 8 caps a year, he should amass

118 caps - although of course at his current rate and uninjured he would gain many more caps.

While deciphering the age potential for Michael Hooper is relatively straightforward, tracking his

actual potential is a vastly different matter. In contrast to College draft picks in America, Michael Hooper is more or less fully physically developed, so this removes any evaluation of his prospective physical development from the equation.

What this leaves us with is the question of whether there is potential for Michael Hooper to improve his skills, leadership or play. In other words can he improve on the things he is already doing? From another perspective, can he improve on perceived or actual shortcomings in his own game? Can he improve his breakdown technique, tackle more dominantly, run more aggressively? Taken this way, a shortcoming shows potential (potential to improve).

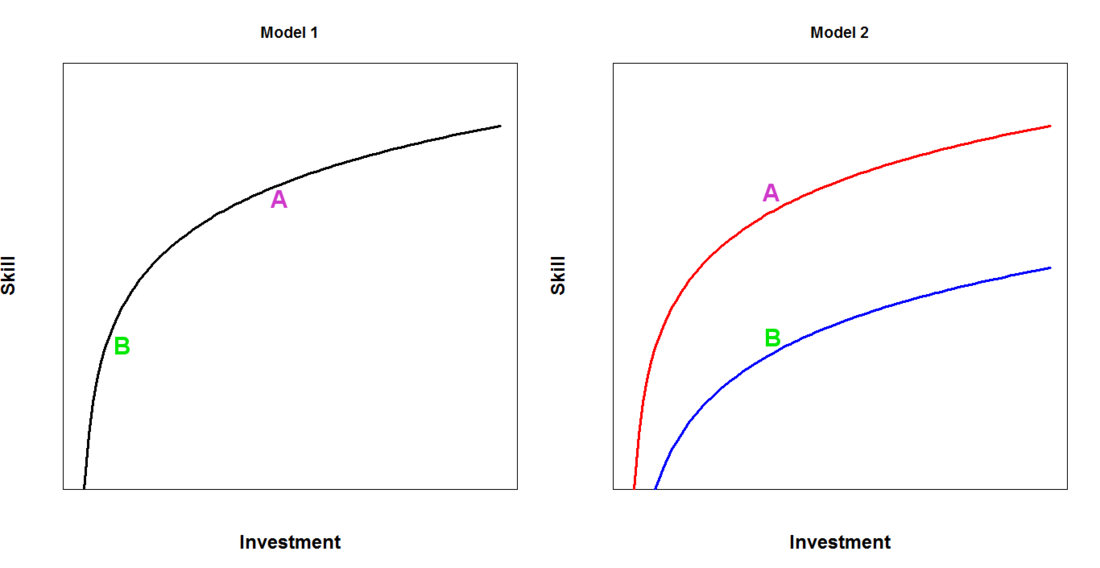

However, the implicit assumption with this approach is that if Michael Hooper can already run aggressively or tackle in a dominant way, he does not have potential to improve in those particular skills. American draft experts describe this as an intuitive perception based on the law of diminishing returns. However, as the graphs below show this does not necessarily need to be the case.

In the above graph, the model on the left shows two players B and A and their relative ability at the breakdown. As you can see, Michael Hooper (A) suffers from the law of diminishing returns as he tries to improve his breakdown work, whereas your average jobber from grade rugby (B) may see significant returns if he decides to go for a midweek run for example. However, model 2 defeats this assumption by assigning the two players to separate curves reflecting the difference in their skills. Here Michael is only compared against himself, ie based against his

fundamental capacity. In fact under model 2, equal investments will result in equal increases in skill. These are two very different ways to model a players potential to improve.

What draft experts in the US have found is that some skills of players conform to the model of diminishing returns (model 1) while others tend to align with model 2 potential. Model 1 skills tend to be

baseline skills such as freethrow percentages, while other skills such as scoring capacity tend to improve in line with model 2 (ie disobeying the law of diminishing returns and improving consistent with the individuals fundamental capacity).

In the context of Rugby, the distinction between the two models becomes important. Arguably, Rugby is a game characterised more by model 2 type skills (breakdown play for example is not as regulated as a goal kick or touchfinder - which would be more analogous to a free throw). This is even more applicable in the context of Hooper who as a 7 specialises in the sorts of skills adhering to the model 2 potential curve.

In short, Michael Hooper has the potential to improve in his skills (even the ones he is already doing well) - of course such improvements would eventually be subject to the law of diminishing returns as model 2 indicates.

Another interesting insight from the US was the concept of player IQ. This does not mean the ability to read a game, but instead refers to the players ability to acquire new skills, pick up training drills, respond to game plans, maybe learn a new skill from a rival.

In the NBA what the draft experts have increasingly found is that players with good statistics across multiple skill traits (can pass well, rebound well, shoot well) have greater development trajectories when they hit the professional ranks than those who are more impressive perhaps physically but more two dimensional. Such high IQ (potential) players are usually identified by their high statistics in forcing turnovers, steals, and assists and their correspondingly poor combine results.

I have not found any equivalent idea in Rugby, but it is not hard to imagine Michael Hooper ticking some of these boxes in terms of his ability to play as an outside back as well as a forward. Further, his young elevation to a leadership role can be seen as evidence of particular aptitude for leadership, reading the game etc.

I understand that this article hasn't come to any concrete conclusions on the likelihood of Michael to improve greatly during his projected career. To properly apply some of the models I have come across, we would need a raft of statistics, which unfortunately at this stage are not publicly available in Rugby.

However, if there are conclusions from this article they would be this:

- From an age perspective, Hooper has the potential to play for another ten years (this much perhaps obvious). The weight of experience (assuming it is good experience) has the potential to prove very valuable to the development of the Wallabies and to himself.

- From a potential perspective, Hooper has the potential to improve in areas of his game which we would perhaps already define as a strength (linebreaks, run metres, points). While shortcomings (likely in my opinion to be model 2 type skills) will also have the potential to improve, it could be the case that Hooper's skills in these areas may be incapable of reaching other players levels (ie he is the lower curve in the model 2 graph above).

- Michael appears to be a player with a high player IQ. I believe in a Rugby context this is evidenced by run metres (identification of space), linebreaks (positioning of body through contact, and successfully running lines as part of planned moves) and also elevation to leadership capacity. This speaks well for the trajectory of his potential improvement.

Where do I stand on his potential to improve given his age, and the pundits who use this argument? I mean, he is young he has already achieved much, he could achieve more. It has an intuitive logic about it, but that is not the same as saying it is logical, he could very well be worked out, plateau, regress or be replaced as discussed above. However, if I had to fall on a side of this argument, it would be that Hooper is very likely to improve as time goes on. He has the dual benefits of a likely long career, plus what American draft experts call pedigree (John Eales Medal Winner, Rookie of the Year, Waratahs player of the year) - these players tend to go on to greater things (evidenced by their high draft picks). So, fingers crossed for Wallabies fans (and Rugby fans) that he does continue on the upward curve.

John